A deltiologist is someone who collects postcards. I have spent more than 50 years of my life as a postcard addict roaming the world, always on the lookout for the little piece of pasteboard that would complete my collection, add another valent to its scope, or just plain make me smile with delight.

My first postcard collection was made on my first trip to Europe in the summer of 1963. Then, I traveled with my parents. Faithful tourists, we had divided out souvenir tasks into three disciplines: still photographs, slides, and movies. It was an extremely well-documented trip, but it was truly notable because, like many tourists had in the past, I discovered postcards. I became obsessed with the pasteboard rectangles, amassing a collection of the wish-you-were-here views as we traveled. There was the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Baptistery in Florence, and Michelangelo’s David—multiple views! I also began to collect images of the works that I loved in the museums we visited, of my favorite street corners, and more.

From left: The cover of Harris’s book; Zulus at mealtime

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

That collection is long gone, thrown out in one of the many purges that have marked my life. The images were the usual ones notable for nothing more than the fact that they were the catalyst that brought me to postcard collecting in earnest several decades later.

That journey would begin as I was working on my doctoral dissertation. The subject was the French-speaking theater of Senegal, and I journeyed to the West African nation to do my preliminary research. In the early 1970s, a Frenchman named Michel Renaudeau lived on Gorée Island off the Dakar coast. I never met him but heard that he’d created several books of antiquarian postcards of West African scenes from his own postcard collection. I found a copy of one of the books in a Dakar bookstore, and with one glance I was hooked on the older postcards, realizing that they presented a vivid photographic memorial that documented the way things were as nothing else could. Many were images taken by François-Edmond Fortier, a Frenchman whose name I did not know at the time. In his images, the dusty streets of Dakar’s past sprang vividly to life.

Coconut pickers, Puerto Rico, date unknown

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

My friend Carrie Sembène (the then wife of the late Senegalese filmmaker [Ousmane Sembène]) was an expert in all great things Dakar. She introduced me to an antique shop on a side street in the center of town. The small shop sold everything from intricately carved wooden bowls and old musical instruments to vintage hand-cut eyelet Goréenne shifts in pristine starched cotton. There, amid the dresses and the bowls and the rest, lurked a tattered box of postcards. I found one or two that I loved and purchased them, but it soon became obvious that my graduate student budget couldn’t stretch to more than a few. I illustrated my dissertation with images from the postcard books and those few cards that I managed to find in my Dakar wanderings. But I became determined that I’d find a way to begin a true collection of antiquarian cards of my own.

As often happens, life intervened. My love of postcards was put on hold for a few years until, as a journalist for Travel Weekly newspaper in the early 1980s, I was selected to go on a two-week bus trip through Belgium and France. The trip began in the Low Countries—Brussels to be exact. We did the usual things: a tour through the Grand-Place, a chocolate factory visit, a walk by the Mannekin-Pis, and more. We also visited the flea market at Sablon. There, I saw my first European postcard vendor.

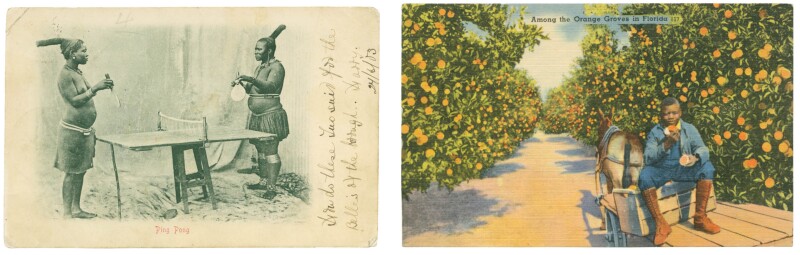

From left: Ping-pong, mailed 1903; among the orange groves in Florida, date unknown

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

Gathering grapes near Cape Town, mailed 1907

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

From left: Norfolk natives, mailed 1915; a Dahomean beauty, mailed 1908; banana carrier, Port Antonio, Jamaica, mailed 1909

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

The person’s stand was unlike the others; rather than the rich display of porcelains or furniture, glassware or rugs, this stand was nothing more than folding tables topped with filing boxes. One glance inside the boxes revealed the treasures. Each of the well-marked boxes contained postcards, masses and masses of old postcards of the kind that I had seen in Dakar. It was my “aha” moment. Of course! Postcards were designed to be sent home! Home for most of the colonists was Paris or London or Brussels. There were more likely to be more cards lurking in attics and scrapbooks in Europe than in Dakar or Point-à-Pitre. I had learned where to look and so another phase of my collecting had begun.

In retrospect, there seemed to be a decade-by-decade ramping up of my postcard mania. The next huge jump would occur in the mid-1990s. My writing career had taken off in quantity, if not in cash, and I was at work on my fifth cookbook, The Welcome Table: African American Heritage Cooking. I was charged with finding illustrations to complete the work. I knew I wanted line drawings; that was no problem. But, I also knew that I wanted a few archival images that would convey the depth of history and give a picture of the past. Again, as I had in my dissertation, I turned to the vivid evocations of the past that postcards provided. However, to my horror, I was reduced to renting images from the usual photo stock houses at fairly expensive fees. It was the moment I was subconsciously waiting for. I finally had an excuse to purchase the cards that had long intrigued me. The logic that unleashed the dam of acquisition was why “rent” images when, for the same amount of money or often even less, I could own the image—my own little pasteboard piece of history? I was off and running.

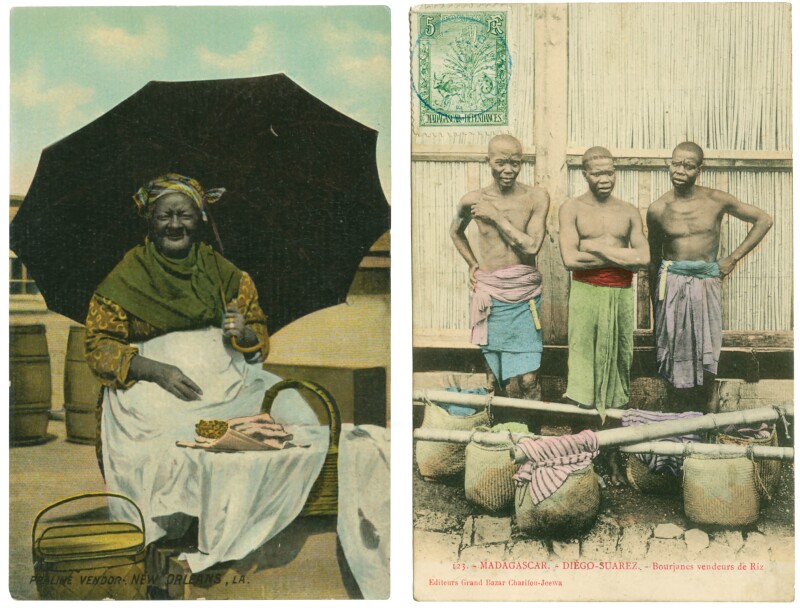

From left: praline vendor, New Orleans, date unknown; Bourjanes rice sellers, Madagascar, mailed 1908

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

Today, with way too many shoeboxes crammed full of cards in their archival sheathes and a file of ephemera, a fair knowledge of postcard history and their background, and a collection of research and reference books to guide me, I can say that I collect in six different categories. I have a collection of postcards about the city of New Orleans that shows that city’s growth and development, another on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, and a small number of cards of old New York City. These collections represent my curiosity about the history and development of the places where I live and have personal history. Cards of early-twentieth-century Paris and others of the same period of France and England speak to my love of history and my career as a former French teacher. One I simply call “Beautiful Women,” speaks to my love of costume, textile, and the study of feminine adornment, while another contains images of the cotton belt of the American South, a subject of equal fascination.

The bulk of the collection remains images of Africans and their descendants in diaspora and their connections to food. Years ago, I broadened it to depict not only labor, but also festivities, dances both real and posed, religious ceremonies, and more—in short, the full scope of a wide section of the history of Africans and the African diaspora in the dignity of their work and the joy of their play.

From left: prayer, mailed 1904; A society cakewalk of the “Upperten duskies” of the New South, Newport News, Virginia, date unknown

Courtesy Vintage Postcards from the African World; copyright Jessica B. Harris

I wish I could say that I am no longer collecting cards. However, I still journey to Vanves and to my favorite shops each time I am in Paris, and I am always on the lookout for cards in used bookstores and at ephemera dealers. I occasionally dip into some internet sites that I trust, and my two most recent cards are from them. If there were a postcard-buyers-anonymous group, I’d have to stand up and admit that I’m a postcard collector and I’m always on the lookout for a yard sale, boot sale, or vide grenier whenever I travel. I find it impossible to pass up a gorgeous card. I guess that’s why I am a deltiologist.

Jessica B. Harris is the author, editor, or translator of 17 books. In 2020, she was named the recipient of the James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award.

>> Next: The Many Sides of Black Paris (and How to Find Them)