Peruvian pisco is definitively, irrefutably the one and only pisco in the world.

I was thinking this as Johnny Schuler, a top Peruvian pisco maker, known widely as Mr. Pisco, plied me—or perhaps poisoned me, given that this was our third bottle—with his chilled, ultrapremium Pisco Portón. The rotgut mistakenly called pisco that comes from Peru’s richer neighbor to the south had nothing on his hooch, I assured him. But wait. In my ebullient haze I somehow realized that, a week earlier, I had been feted with Chile’s best pisco by Santiago’s answer to Johnny Schuler. And I recalled, as in a traitorous déjà vu, agreeing at the time that Chilean pisco was the way, the truth, and the light.

This kind of metaphysical confusion was a hazard of the job I had chosen. I had decided to take on one of the most serious and long-standing geopolitical disputes of our time: Should Peru or Chile have the right to claim pisco, the brandylike distilled wine that is South America’s most famous spirit, as its own? Both countries have legitimate arguments. The original town of Pisco is a port in southern Peru. But Chile exports much more of the spirit and has a town of its own named Pisco Elqui (though it was called La Unión until 1936).

To claim the liquor as its own, in my view, a nation has to show that pisco is part of its soul.

The stakes are high, starting with the all-important cultural bragging rights. Just as true Champagne can come only from France, Peruvian pisco makers would like to say that true pisco can come only from Peru. Chileans would claim the distinction for Chile. Pisco producers also hope their offerings will join the ranks of vodka and tequila as staples of global barrooms, with the booming sales that would be generated. Even though pisco is still relatively obscure, if either country were forced to abandon that appellation on its exports, the loser would have to retool its marketing completely.

And so, in addition to my own pisco-polluted one, there were other bodies on the case: The European Union and the WTO were already deliberating, and drunken rumors floated around Lima and Santiago that Greenpeace, Amnesty International, and the International Criminal Court might join the fray. If I wanted to resolve this heretofore intractable dispute my way, it was time to act. I would subject myself to as many different piscos and pisco cocktails as I could, in situ, before the big guns weighed in with pisco policy papers, press conferences, and Security Council resolutions. I needed to experience the totality of piscodom in both countries, to peer beyond the eggy froth of a pisco sour and examine the bars and barrels, the cocktails and culinary combinations, the popular and elite ways of drinking. To claim the liquor as its own, in my view, a nation has to demonstrate more than just provenance or precedence. It has to show that pisco is part of its soul.

So, in the name of justice, I had set out for the Andes with an open mind and, I hoped, a resilient liver.

Pisco sour at Ciro’s, Santiago, Chile

Photo by João Canziani

Santiago, Chile, is a city of high-rise luxury hotels and condominiums that all look gleaming, modern, and safe. For my first pisco sour, I ascended to the rooftop bar of my hotel, the Noi Vitacura, and met with one of Santiago’s preeminent bartenders, Luis Felipe Cruz. Luis looked so young that I would have carded him if I’d been working the door. However, he quickly demonstrated his bona fides by mixing up a few fresh, original, fruity pisco drinks. These alone would have made my visit worthwhile. But I soon learned that Luis wasn’t just the most skilled and knowledgeable pisco bartender in Santiago—he also happened to be half Chilean and half Peruvian. Which meant he might be the one man capable of impartially elucidating the facts on the ground. He poured a range of the world’s best piscos, mostly Chilean but a few Peruvian, and we started to drink.

Pisco begins with a base liquid produced with methods similar to those used to make wine. The liquid is then distilled over heat to concentrate the alcohol. There are two very obvious differences, Luis pointed out, between Chilean and Peruvian pisco. First, Chile allows its piscos to be aged in wood barrels, which can impart a brown color and a variety of flavors beyond the taste of the distilled grape base. The barrel-aged pisco that Luis poured me, top-end Mistral Gran Nobel, was rich and complex. (And eye-opening. The pisco cocktails I had drunk back in the States all used the clear type.) However, most Chilean piscos are, like all Peruvian piscos, aged in neutral containers made of metal, glass, or inactive wood, so the liquor can rest after being distilled. This process yields a clear distillate that lets you taste the grapes straight and fresh, without tannins or extensive aging.

The second difference, Luis explained, is that Peruvian piscos have to be distilled “to proof,” while Chilean piscos are distilled to a higher alcohol percentage and then diluted to“bottleproof.” I asked Luis the obvious question: How does this affect taste or texture? “It’s really impossible to say,” he told me. “Truth is, the only way you could see what the real differences are would be to distill the same wine both ways and compare. But no one wants to do that and run the risk that the experiment might prove the other way is better.”

I realized she was looking for something from me, some gesture to affirm her—and Chile’s—claim to pisco.

After my visit with Luis, I went to a tasting room at the top of one of Santiago’s tallest buildings and met Claudia Olmedo. A pisco sommelier, she works for the giant Chilean conglomerate that owns the popular pisco brand Control and many others. Claudia laid out an array of her company’s best piscos, starting with Control C, a triple-distilled, premium export product, and ending with a pisco from Horcón Quemado, one of the small, boutique brands her company distributes.

I was eager to start sipping, but as I reached for a taste, Claudia motioned for me to wait a moment. She then began to tell me about Chile’s historical claim to pisco. In the 1500s, she explained, the Spanish brought grapes and the art of distilling to a region that extended into what is present-day Chile.

She paused in her narration, but once again warned me off the pisco with a stern glance. I realized she was looking for something from me before I’d be allowed to touch the booze, some gesture to affirm her—and Chile’s—claim to pisco. It seemed Chile wasn’t asking for much, just the right to use the name along with Peru, and from what I’d seen so far, the country produced some good stuff. So, in one fluid motion, I formed my left fist into a sign of solidarity with her cause and darted in with my right to grab a small snifter of Control C. It was extremely smooth and tasted of citrus. I snuck in a few more sips, and as I warmed to the pisco, Claudia started speaking from the heart.

“The worst injustice of all perpetrated against Chilean pisco,” she said, “is that they won’t even let us call it by its name.” In Chile, the Peruvian brandy can be called pisco, but in Peru, the Chilean liquor is rechristened aguardiente, a catch-all Spanish term for firewater. Nobody likes a linguistic bully. Censorship is a sign of weakness. I took another sip of Control C and decided then and there that I wouldn’t let the Peruvian pisco dictatorship control me. I was throwing in my lot with Chile. At least for now.

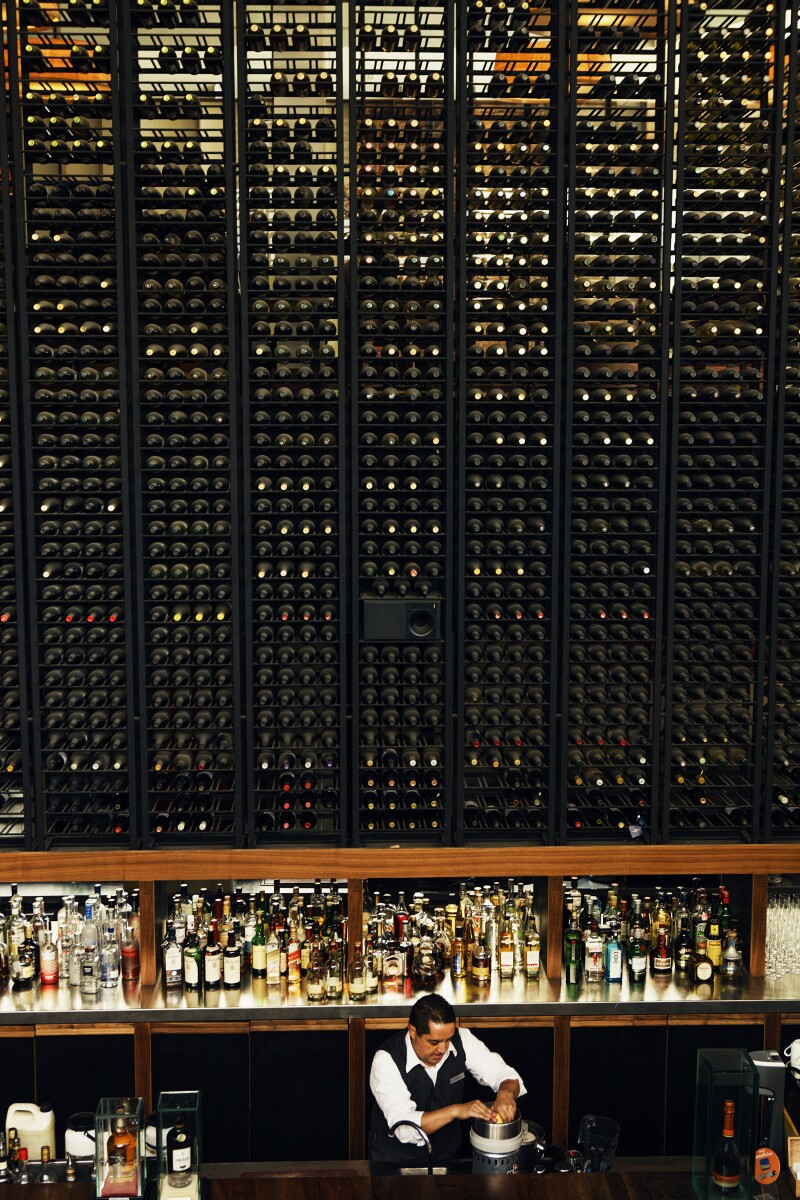

Inside the Hotel Noi Vitacura restaurant, Santiago, Chile

Photo by João Canziani

Santiago had been an important first stop on my journey, but the cosmopolitan metropolis felt a bit too comfortable for my purposes.

So I set off for Valparaíso, where, I was assured, I would find more dirt, more dive bars, and a glimpse of Chilean pisco’s soul. Though just a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Santiago, Valparaíso is foggy and forgotten, a place to seek out when you want to escape from the world as you know it. Down near the water, where drunken punks line up with their friendly pit bulls to buy late-night hot dogs, and old Italian-Chilean couples whose semiformal attire hasn’t changed for half a century stroll the street, I found a couple of bars that oozed Chilean authenticity. As I entered Bar Cinzano, I was swept by a wave of nostalgia for an era I’d never even experienced, courtesy of a tango band that looked as if its members had been pickled in the 1950s. I asked for a pisco sour. The tuxedoed barkeep dug his long spoon into a towering mound of powdered sugar and mixed up a dainty cocktail. I detected a key difference between Chilean- and Peruvian-style drinks. He used just powdered sugar and lemon, omitting the raw egg whites that Peruvians incorporate to make their sours foamy. When I asked him how he got the froth without the egg, he paused his shaking and flexed his biceps. The drink he served me tasted especially light.

After my day in Valparaíso, spent bar-hopping from Cinzano to Bar Inglés (an old-style dockside sailors’ haunt) and finally to a clandestine rooftop bar overlooking the city’s hillside of brightly colored metal houses, I felt I’d found the gritty Chilean pisco culture I was after.

Pisco wasn’t born in a research library or a laboratory. It thrives as a living culture in both Chile and Peru.

A five-hour drive took me from Valparaíso into the dry northern region of Chile where grapes are grown, pressed, fermented, and distilled into pisco. My destination was the remote, intensely cultivated Limarí Valley, where I met Jaime Camposano and Juan Carlos Ortúzar, partners in a budding boutique pisco brand called Waqar. Jaime is a pisco prince. His family has been making pisco for five generations, and his grandfather was the president of the Cooperativa Pisco Control, the nation’s largest pisco producer at the time. “Pisco starts here,” Jaime said, pointing to the grapes as we rode horses through the narrow trails of his vineyard. “We distill over a real fire,” he told me. “The operation is very delicate. It’s like flying a plane. You have to know exactly when to do each thing; otherwise the end product won’t be right.”

Jaime grew up watching his father manipulate the alembic, the large, metal Rube Goldberg–esque contraption of pots, tubes, condensers, and collecting vessels used to distill liquids. The pivotal moments in the process, he told me, come when you separate the “head” (the high-alcohol, strongly flavored liquid that first bubbles up) from the “body” or “heart” (which will be made into pisco), and the body from the “tail” or “negative” (the undrinkable dregs).

After we toured the old distillery, we retired to a rooftop and drank the signature Waqar cocktail, a refreshing libation made with rosemary and lime. Waqar is excellent straight, with a fruity, clean, slightly sweet taste. Jaime and Juan Carlos are targeting the cocktail market in the United States and elsewhere outside Chile, which is the main reason they eschew the barrel-aging process that many premium Chilean piscos use. Before I visited Chile, I’d heard from Peruvians in New York and California that Chilean pisco-making was an industry, not an art. But Waqar’s tiny distillery was about as artisanal as it gets. I left Chile with this and other Peruvian prejudices against Chilean pisco punctured, as well as with a vivid, if slightly foggy, notion that I’d experienced a pure and beloved pisco culture unlike any other.

Grape picking at El Pabellón in Horcón, Chile

Photo by João Canziani

When we neared the customs check after landing at Lima Airport, João Canziani, the photographer traveling with me, glanced nervously over his shoulder. I ignored him and hoped the Peruvian officials hadn’t clocked our shifty body language, a sure sign we were smuggling illicit goods. In our case, it wasn’t cocaine or hashish. It was something perhaps even more heinous: Chilean pisco, still bearing that blasphemous label.

Any pisco-inspired visit to Peru must begin with a visit to Johnny Schuler, the aforementioned Mr. Pisco. I met him at one of his restaurants, Key Club. He looked like he’d been transported from a Rat Pack–era Las Vegas drinking den. “I’ve had restaurants for years,” Johnny said, as he settled in at the table and took a sip of a pisco sour. “And I’ve always been a pisco fanatic. But I only started making pisco in the last three years, with Pisco Portón.” Before we ordered another round, Johnny cautioned me. “Pisco sours are so sweet, you can only have two at most,” he said. “More than that is dangerous. After two you have to switch to straight pisco.”

I followed Johnny’s advice and, after two sours, moved on to the straight stuff. Portón smells great, like ripe grapes. The ultra-premium mosto verde version we drank was very sippable. Over a dish of citrusy ceviche, I deftly switched the conversation to the elephant in the room, and in our luggage: Chilean pisco. “Tom, you have to understand, it’s a different thing. It’s not pisco. Pisco is ours. Pisco is from Pisco. That’s in Peru,” Johnny said definitively. “Plus it’s not the same grapes. It’s not the same process. It’s totally different.”

“Johnny,” I protested, “have you tasted any of the good stuff coming out of Chile now, like Waqar or Control C?”

He refilled my glass and ignored my question, foreshadowing his strategy. Unlike Claudia in Chile, who withheld her pisco as an incentive for me to agree with her, Schuler engaged me in a pisco war of attrition, in which I would eventually have to concur with him on Peruvian pisco’s preeminence, or be incapable of disagreeing.

Horseback riding with Jaime Camposano and others in Chacay, Chile

Photo by João Canziani

I was up for the challenge. And, though I don’t remember much more of our exchange except that it involved a lot more Pisco Portón, I am certain that, in the end, I didn’t let Chile down. Or Peru down. Or anyone down. At least I don’t think I did.

Bar Inglés at Country Club Lima Hotel in the city’s upscale San Isidro neighborhood was a good place to go the day after a nightlong pisco propaganda session. The room was paneled in warm, dark wood and filled with comfortable leather chairs. Most important, the music wasn’t too loud. I found Roberto Meléndez presiding over the bar and noticed, to my chagrin, that his deputies were mixing pisco sours in blenders, which, to my mind, produces a cocktail that is way too frothy and too uniform in texture. I told Roberto so, and he agreed, but he explained that the bartenders have to churn out so many pisco sours every night that it would be impossible to mix them all by hand. He dusted off his cocktail shaker and made one for me. “I use just one-quarter of one egg white per drink,” he said. “That’s all you need. The key is to start with good-quality pisco, use fresh lemon, and not make the drink too sweet. It’s meant to be an aperitif, not a dessert.” I sipped Roberto’s drink, and it was a revelation. The lowered sugar content let me actually taste the pisco and the lime.

At the bar I met Carlos Mujica, a friend of João Canziani’s father and himself a pisco maker. “I don’t make pisco as a business,” said Carlos, a tall, sunburned recreational sailor in his mid-50s. “I do it because it’s my passion.” He has a small vineyard down in Peru’s Pisco region that he cultivates each year. The thousand or so bottles of pisco he manufactures are for friends and fellow pisco aficionados. Carlos represented another aspect of the pisco culture I’d been seeking in Chile and Peru, because he wasn’t in it for fame or fortune.

“It’s like making wine or running a restaurant,” he said. “It’s the best and fastest way to lose all your money. But who cares?”

The day after talking to Roberto and Carlos, I traveled south to Pisco Province to visit Johnny Schuler’s Portón distillery, an enormous facility called Hacienda La Caravedo, with shiny metal tanks everywhere. Peruvians like to portray themselves as the impoverished underdogs in the pisco war against industrial behemoth Chile. But Pisco Portón, founded by a wealthy Texas-based family, hints at a possible sea change. Though Chile now produces and sells much more pisco than Peru does, a lot of capital is clearly pouring into Peruvian pisco as well.

It was subtle and not too sweet, the vibrant taste of the pisco just peeking out from the unusual blend of flavors.

On my last night in Peru, back in Lima, I visited the barroom at Central, one of the city’s most acclaimed restaurants. Part of what Peru has going for it in the pisco war is world-class cuisine, exemplified by the food at Central, to go along with the cocktails. And Peruvian restaurants around the world afford further opportunities to popularize and propagandize Peru’s pisco.

The first dish I ordered, roasted suckling pig, was so crispy and delicious that, even though I was up to my eyeballs in pisco, I just had to order one last Peruvian pisco drink.

The bartender mixed up one of his original creations, made with passion fruit and cardamom. It was subtle and not too sweet, the vibrant taste of the pisco just peeking out from the unusual blend of flavors. When he asked if I wanted to try a different cocktail, I nodded. Though he had all kinds of exotic offerings on the menu, I knew exactly what I wanted. His classic pisco sour. It was frothy, citrusy, and had exactly the right amount of sweetness to complement but not overpower the bite of the grape liquor.

After one sip of his second concoction, I looked at my watch. Only by a frantic rush to the airport could I catch my flight back to the United States. I cashed out and caught a cab, but even with my driver’s high-pitched horn desperately trying to clear the congestion ahead, I missed my plane, all for the sake of sampling another high-class pisco sour. And I didn’t even get to finish the drink.

Vitivinicola Fundo Los Nichos, Chile

Photo by João Canziani

Back home in New York, I did what I usually do after an international fact-finding mission. I procrastinated endlessly. Partly, I was hoping that some other body would release a policy paper I could pounce on, rather than elucidating an independent stance of my own. My waiting paid off that fall when the European Commission handed down its decision, which granted Peru exclusive Geographical Indication status, acknowledging that the brandy originated in the Peruvian region of Pisco. But the Commission also decreed that Chileans can still call their spirit pisco.

From a commercial perspective, the ruling means little. Since Chile can still use the contested name, probably the only consumers who will notice the difference are those who actually read all the fine print on the bottle. Nevertheless, it’s a blow to Chilean pride. Pisco wasn’t born in a research library or a laboratory. It thrives as a living culture in both Chile and Peru, whatever the pisco nationalists might say.

I wonder whether the authors of the bland 2013 policy edict have ever sampled pisco on a secret rooftop bar in Valparaíso, or been drunk under the table by a man known as Mr. Pisco, in Lima. Until they have, I conclude, they don’t know from pisco.

This article originally appeared online in February 2014; it has been updated to include current information.>>Next: The Czech Cocktail That’s Actually Good for Your Health