In 2020, I spent months researching the life of pioneering aviator Lilian Bland. I’d known of Bessie Coleman and Amelia Earhart, sure, but as I learned more about Bland, I realized how unfamiliar I was with the myriad other women who had made aviation history. Off I went, full throttle into the achievements and legacies of women pilots like Florence Klingensmith, Amy Johnson, and Katherine Cheung. At a time when I wasn’t flying, soaring and spinning through the sky via the escapades of these women was a fitting substitute—no airsickness included.

It is hardly surprising, then, that I tore through my copy of Maggie Shipstead’s ambitious new novel, Great Circle—our May AFAReads selection—which weaves together the stories of two women: famous aviator Marian Graves, who disappears on a flight to the north and south poles, and actress Hadley Baxter, who is hired a century later to portray Marian in a film. Even though the two women are separated by time and geography, we come to know more about each one through alternating perspectives: Marian’s story told in third person, Hadley’s in first. We feel their closeness as they share similar struggles and ambitions.

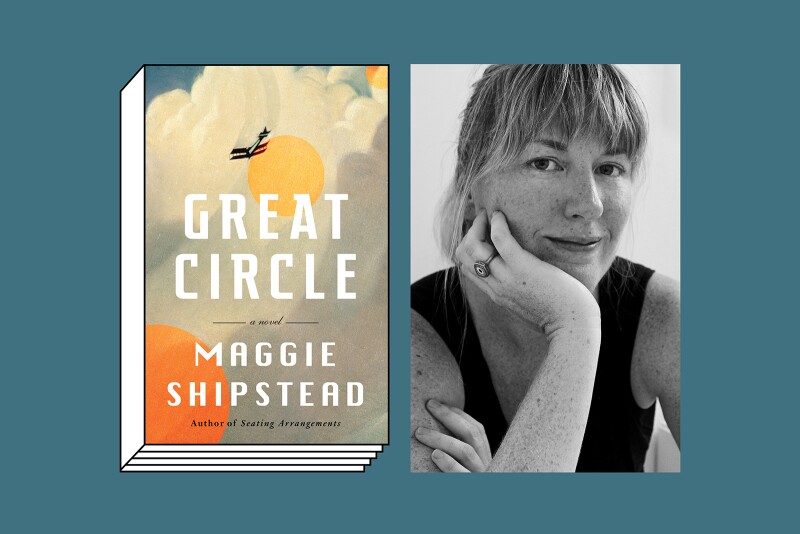

Shipstead is best known for her two previous novels—her bestselling debut, 2012’s Seating Arrangements, and 2014’s Astonish Me, winner of the Dylan Thomas Prize—and says she’d been working loosely on another novel when she had the idea for Great Circle. We sat down with the writer to learn more about her inspiration behind the book and how she folded in her own real-life travel experiences.

Author Maggie Shipstead, who has also published “Seating Arrangements” (2012) and “Astonish Me” (2014)

From left: Courtesy of Knopf; Maggie Shipstead

Buy now: Great Circle; bookshop.org

Take us back to the beginning. How did the idea for Great Circle come about?

Back in 2012, when I first started traveling by myself, I sort of puttered around the South Island [of New Zealand] for three weeks. Seating Arrangements had come out and I was in edits for Astonish Me, and I had brought the beginning of another novel with me on the trip. And during that time, the novel I thought I was going to write just died on me. So by the time I got to the airport in Auckland to go home, I was feeling a little dejected and open to ideas. And so I saw the statue of [aviator] Jean Batten and that quote from her on it—that “I was destined to be a wanderer.” And I thought, “Oh, I should write a book about a female pilot.” For some reason, that struck me as inarguable. I didn’t really start writing it for another two years—until fall of 2014—but I had it in my head as my next project during that time.

When you did start writing it, what other women aviators did you look to for the story?

I cast a pretty wide net. I was interested in Amelia Earhart, partly because—to me, and I think to a lot of people—it seems abundantly clear that she crashed into the ocean and drowned; that that’s by far the most likely scenario. It’s a really obvious explanation and anything else would be extremely unlikely, but I think it’s interesting that this pseudo mystery has persisted for so long. So I became interested in this question of: “What’s the difference between disappearance and death, or how do people process them differently, even though they’re often the same thing?”

I read her books that she’d [Earhart] written and I read a biography of her, and same with Beryl Markham. I read a biography; I read West With the Night. Of course, I read de Saint-Exupéry and I read Charles Lindbergh—whatever I could come across. And then I read about more obscure pilots like Eleanor Smith and Jackie Cochran. I tended to research as I went along, so I’d come to a question and then order a bunch of used books that would hopefully answer it. My research was really piecemeal.

What are some facts that you discovered during research that have stayed with you—that kind of blew your mind?

That Charles Lindbergh was at the launch for Apollo 11 was incredible to me. I think that shows the speed at which this technology developed and changed the world. Someone sent me a scan of a letter Lindbergh wrote to [astronaut] Michael Collins, almost envious for his having experienced the aloneness of orbiting the moon by himself while everyone else was on the moon. Which is a deeply Charles Lindbergh thing to do.

Also, a lot of what I learned about the women who flew war planes—who transported them for work during the war—I really didn’t know before. They had such interesting lives, and flew so many different kinds of planes. Even the way they were taught to fly is fascinating.

What purpose did Hadley serve to you, as a character and narrator?

I wanted Hadley in there partly as the lens on just how much life is lost. No matter the circumstances, you know, no one else can know more than a tiny fraction of what you experienced in your own life. Especially over time and removed by a couple degrees of separation.

The book took about six years, from inception to completion. In what ways did the book turn out differently than you’d imagined it?

I am incapable of planning or outlining a novel, which makes it sort of a nightmarish process in some ways. My previous books had both started as short stories. So this was the first one I wrote knowing it would be a novel. I kind of just jumped in, and I had no notion of it being as long and complex as it is. I really just started with the idea of the pilot, and I knew I wanted her to fly during World War II, although I hadn’t decided if that would be in the U.S. or in the U.K. I thought of Hadley pretty early in the writing—within a couple months—and then also the sort of incomplete history sections.

But as constantly evolving as it was, I struggled the most with Hadley’s arc and how tightly it should be connected to Marian’s. The end result is absolutely nothing I thought I was embarking on and it was incredibly overwhelming process. I think I got two years into writing the first draft, and had written something like 400 pages, and it dawned on me that I was not halfway through. And that was sort of a dark day. I realized how much more there was to be done. I had to find a way to understand that the only way out was through and to do a little bit every day and just not think about the whole. Maybe there’s an analogy there to Marian’s flight. You just have to sort of take it one step at a time and keep going.

Missoula. Antarctica. New York. Alaska. Seattle. This book moves through so many destinations, which are presented so vividly. How did these places dovetail with where you’d been traveling in real life, and how did those experiences inform what appeared in the book?

It was really deeply symbiotic. I started writing the book in fall of 2014 and then I started travel freelancing in 2015. I was chasing assignments that were places I wanted to see for the sake of the book. For example, it was very important to me to see Antarctica, and to understand what the Antarctic ice sheet looks like. I don’t think I could have grasped sort of the precarious feeling of it and the scale of it without having seen that.

Where did the title of the book come from, and how is it reflected in Marian and Hadley’s stories?

I had it from the beginning, which was not true of either of my other books. It’s funny, because everyone wants to call it The Great Circle. But it’s not just about the circle that she’s flying—it’s about the way life loops around. The structure of the book even has a bit of a circular form. It attends to this question of, you know, that she departs on this circle and it’s going to be this grand achievement, but at the same time it delivers her right back to where she started. So maybe that’s the essence of the journey being the point.

[Note: Book spoilers in this answer] How did you decide on the book’s ending, and Marian’s fate?

For most of the book, as I wrote, I hadn’t decided what would happen to her. I didn’t fully decide until I had to, which was fairly late in the game. My reluctance to allow her to survive actually had to do with my feelings about Amelia Earhart. But I sort of decided I’d killed off enough characters and also that she would still be paying a fairly terrible price for what happens in so many ways.

What do you hope readers feel when reading the book?

I have to say it’s shifted a bit because of the pandemic, which I couldn’t possibly have anticipated even when we set the pub date. I think everybody is just so hungry for freedom and movement and to see new things and to experience novelty. So I hope that people kind of have a good long think about what in the world they want to see and what they want to experience. I am still surprised sometimes when I realize that I can actually go places that I want to see.

We see a lot of the characters in the book pushing boundaries. How do you think travel enables us to do that?

Travel, for me, has little by little expanded my comfort zone and then also expanded the liminal area just beyond my comfort zone where I’m willing to go. And I think the more experiences you have, the more open you are to continuing to have new experiences. I’ve always been afraid of deep water, but I pitched an assignment for Travel & Leisure to swim with whales in Tonga. I knew I wanted to do it, but I also knew I was totally terrified. That first leap into the water was like, Am I going to panic? I don’t know. But then once I did that and it was amazing, it opened me up to other things and changed my perspective on what I could do. And I think that happens for a lot of people, whose curiosity is continuously stoked by their travel. Unfortunately, it seems like often people also have to see a place to kind of understand it’s important, and to care about it.

How has the pandemic changed the way you think about travel?

Certainly it’s reminded me that not all things are possible all the time. You know, I don’t think it ever occurred to me that there would just be a year where I couldn’t go anywhere. There’s a reminder to appreciate our ability to move around the planet and to encounter new people and new things. So I hope that I’ll have more appreciation when I get back to it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

>> Next: The “Flying Feminist” Who Was the First Woman to Design, Build, and Fly Her Own Plane