To kneel into the snow of a steep mountain face can’t help but look like an act of prayer. It felt like one, too. I had climbed several thousand feet up an active volcano. My chest faced the summit, and avalanche beacon strapped below my heart. Please, I thought, don’t let me turn around too fast, tumble down, and break my neck. Please help me remember that I was about to go surfing, in a manner of speaking.

Mount Yōtei is about 6,000 feet high. On Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, it’s known as “Little Fuji” for its resemblance to the bigger mountain. But Yōtei doesn’t feel small when you’re calling on the gods. For several hours on a bright February morning, our party of 10 had snowshoed up ridges, through ghostly birch trees, to reach the vertiginous final stretch before the summit. We huddled on a slab of hard-packed snow, snowboards strapped to our backs. Our lead guide, Makoto Yamada—Mako for short—surveyed the scene and frowned.

I grew up in love with the snow. Part of the reason I went to college in Maine was that the school’s catalog featured a quote from Oscar Wilde: Wisdom comes with winters. It didn’t hurt that students got a heavily discounted pass to a nearby ski resort. For a time, snowboarding was my thing. Fifteen years later, I’d lived in New York and Paris, and I had gradually lost interest. It was too expensive, too difficult to arrange, not exactly accessible by subway. The sport didn’t seem appealing anymore. I’d always enjoyed it for the alpine moments, gliding down the mountain. When I watched the Olympics or the X Games on TV, with guys flipping through the air, it looked like a frat party for teenage acrobats.

On Hokkaido, the volcano wore an enormous gray cloud like a fez. The sky was darkening. If we were going to summit, we needed to move. Mako shook his head, glanced down at me, and said solemnly, “We drop in here.”

In Hawaii’s surfing culture a shaka—the international sign for “hang loose”—conveys aloha spirit: friendship, understanding, compassion. But when your mountain guide throws one while standing on the icy flank of a volcano nearly 4,000 miles from Honolulu, it reads a smidge more like, “Here we die!”

Thus I was inducted into the Japanese art of the “snowsurf.”

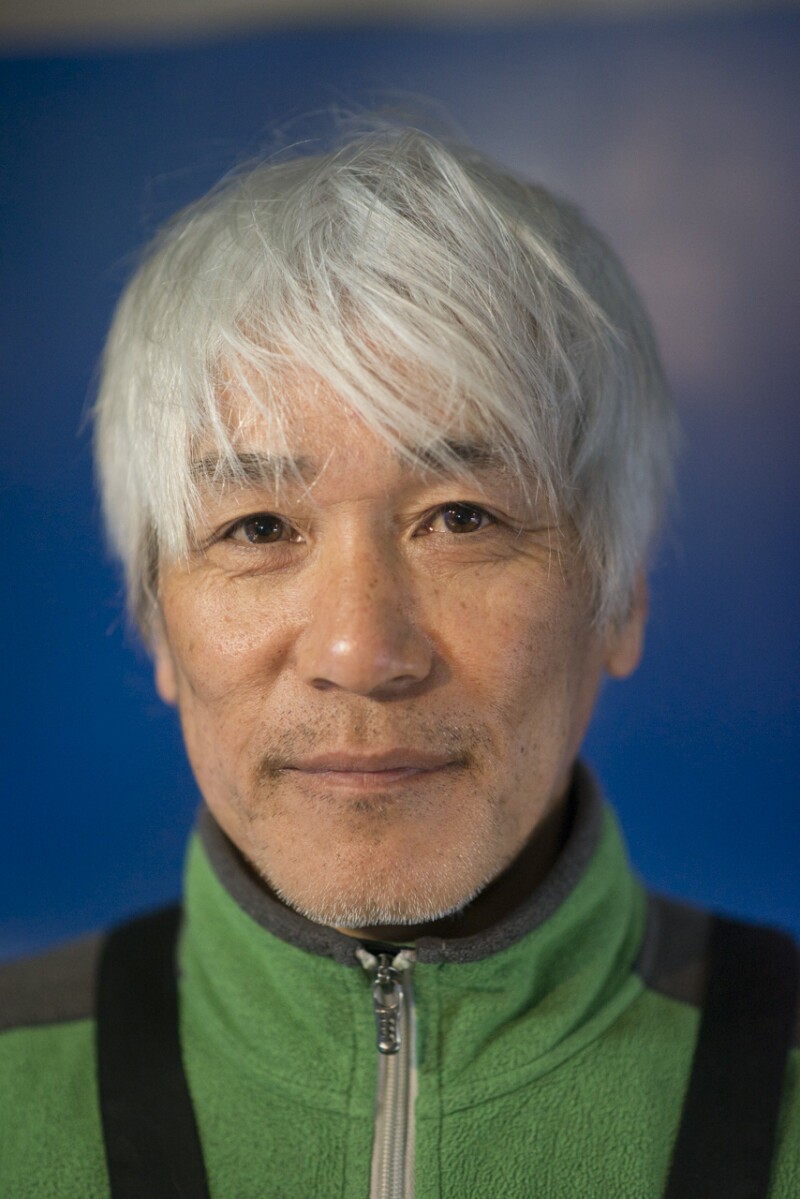

Photo by Kari Medig

Hokkaido is Japan’s second-largest island, the northernmost of its 47 prefectures. It’s chiefly rural, with dazzling natural beauty. A huge terrain of blue lakes, snowy pinnacles, and rolling hills, the land is bordered by the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Pacific Ocean. It’s water, water, everywhere—and the water is put to good use. Surfing spots abound in summer; same for fishing and rafting. Hokkaido’s seafood industry supplies the fish for much of Tokyo’s, and the world’s, sushi.

As I rode a bus into the mountains from Sapporo’s New Chitose airport—Sapporo is the island’s capital, plus the birthplace of the eponymous beer, another good use of water—signs appeared regularly on the highway advertising the island’s famed onsen, natural hot springs where mineral waters bubble up through the earth.

But what lured me to northern Japan was snow. Hokkaido is a powder kingdom, each peak a Mount Olympus. Friends who were hard-core skiers and boarders had been talking about it for years. How storms from Siberia, one after another, entomb the island with a powder snow so dry and fine (search for #jappow on Instagram) it turns the act of skiing or snowboarding into something more like, well, surfing. Through clouds of the stuff. If clouds were tethered to the ground.

Which is one reason why Hokkaido is now considered the cradle of snowsurf culture. It’s a style of snowboarding that, when I first heard about it from a friend, seemed to encapsulate everything I’d always loved about the sport. In essence, it emphasizes the elegance of turns. You concentrate on your “line,” the path you sculpt from the slope. The rider’s bond with nature is through earth, not air. The style is identified with the Japanese snowboard designer Taro Tamai, who lives on Hokkaido and is perhaps the movement’s best-known rider and popularizer, and also its reclusive monk.

Hokkaido’s skiing is centered in Niseko, about 60 miles southwest of Sapporo. I arrived on an unusually sunny day. Niseko is a village, but it’s also the name people use to refer to the region, where a cluster of tiny hamlets lies below “Niseko United,” a group of four ski resorts spread across the many peaks of Mount Niseko Annupuri. The area receives one of the largest dumps of snow of any resort in the world, with an average annual total of 50 feet.

Photo by Kari Medig

The day after I arrived, Taro Tamai and I met at his showroom. It’s a short walk from the center of Hirafu, Niseko’s most developed community. Where other villages nearby are sleepy and homespun, Hirafu is a tiny resort town that contains Michelin-starred restaurants and boutique hotels, as well as food trucks selling fish and chips. Perhaps #jappow was once a secret—the first ski lift appeared in Niseko in 1957—but it’s been embraced for at least a decade by boarders from Hong Kong to Colorado and, especially, Down Under. When I walked into Taro’s showroom, a young Australian was trying to convince the woman behind the counter that he really, really needed to meet Taro. Please, he pleaded, he’d come so far. The tiny shop was jammed, full of people gazing at the snowboards and surfboards as if they were works of art. The woman said Taro was busy. The guy looked crestfallen. He said, “Please just tell him how much we appreciate him. For putting all these beautiful things into the world.”

Taro used to be a top professional snowboarder, making first descents on giant mountains in Alaska. But eventually he returned to Japan, he told me, to make boards no one else was making—boards that have since developed a cult following, as much for their beauty as for anything else. (There’s a reason the catalog for Gentemstick, Taro’s company, notes, “Use the board as much as you can, and never waste it just as an interior decoration.”) Taro designs boards unique in part for their minimalist aesthetic—bamboo boards, wooden boards, boards sporting swallowtails like surfboards from yesteryear. But what really draws riders to the brand is Tamai’s viewpoint, his mission to connect snowboarding to its ocean roots.

Taro and I went out for tea across the street. “When snowboarding started out,” he said, “it was about having fun in the mountains. But then it got commercialized.” It sounds cliché, the same sad story of anything that’s ever been cool, but in this case, the narrative actually influenced how the equipment was made. The boards themselves changed. According to Taro, the way was lost when snowboarding began to take after skateboarding rather than surfing, emphasizing jumping over riding, the thrill of leaps over the pleasure of turns. “Snowboarding, when people think about it—all the images are in the air,” he said. “But not everyone wants to do that. Ninety percent of snowboarders want to carve snow. They want to be on the ground.”

Taro sees himself less as a designer than as a shaper, in the style of old-school surfboard makers. He offered to loan me one of his boards the next day. I asked how I should go about snowsurfing, rather than snowboarding. The difference was awareness, he said. Being supple, not brutal. Adapting to the snow rather than imposing myself on it. “Look at the mountain with a surfer’s eyes,” he said. “Look for how the terrain changes.”

When we left the teahouse, it was snowing again. Everything was gray. It would be another day before I was praying on a volcano; for now, I needed some practice on tamer slopes. The board I carried back into town was a handsome blue number with a surfboard’s pointy nose. I actually know how to surf, though I’m horrible at it. Before I left the States, I had called Alex Yoder, a professional snowboarder based in Wyoming, for advice. Yoder recently joined the Gentemstick team, becoming the first American snowboarder to ride professionally for the company, using Taro’s boards during contests and expeditions. I asked Alex to help me comprehend what snowsurfing was all about.

Photo by Kari Medig

“Taro learned how to fish from his grandfather,” he said. “Then he learned how to surf. So he started in the water. How he designs his boards mimics that interaction. Obviously, they’re built for snow; they’re still snowboards. The snowsurfing part of it has a lot more to do with the mindset.”

The next day, I rode Taro’s board down the different ski mountains around Niseko. I dutifully paid attention to the terrain, tried not to impose myself too hard. But what did he mean, really? Michael Jackson and R. Kelly songs blasted around the mountain. (It’s a unique, slightly alarming feature of Japanese ski resorts: the tinny, ever-present soundtrack of R&B.) Plus, the snow was good but not great. For weeks, storms had been epic, but my flight into Sapporo must have scared them away. I’d heard from person after person about the appeal of skiing in Japan—small crowds, great snow, cheap lift tickets. Perhaps I’d set my hopes too high? Taro’s board was a very good board, but it didn’t inspire epiphanies; a snowboard does not an enlightened man make. And the piped-in music was getting on my nerves. That evening, when I walked back through Hirafu, wrapped in snow and the night, all of Taro’s philosophizing felt like New Age blather. Something was missing.

A day later, from near the top of Yōtei, the valley around me was a patchwork of farms, massifs, and trees—a pretty tableau that did nothing to calm my stomach. The wind was fierce, huge flags of snow were being ripped off the mountain. From where we sat, I could see forest and mountains to the horizon, and forest and mountains down between my boots. When I looked into our guide Mako’s eyes, I saw only high-octane anticipation.

Photo by Kari Medig

Thoreau said, “We can never have enough of nature.” It’s what I’d been missing, what I needed—time away from lift lines, back in the woods. I had reached out to Gentemstick, and they’d recommended a guide service called Powder Company, operating from the village of Annupuri. Powder Company specializes in backcountry snowboard tours, in particular using Gentemstick boards. Pretty straightforward stuff on paper: Climb to the top of something, then “surf ” to the bottom. Our party of 10 comprised four guides and six clients. We had met that morning at the guides’ lodge and checked gear. The other snowboarders were all from Tokyo, the guides all Japanese, most of them on one of Taro’s boards. They were experienced backcountry riders, trained in ski mountaineering and avalanche rescue—and they all smiled very politely when I explained, through an interpreter, that I was absolutely none of that, arigatou gozaimasu.Now it was time to go. Mako shouted his plan over the wind: We would descend in segments, one at a time. He would explain where to go, and more significantly where not to— what features to avoid in case of bad snow, tree wells, or other hazards. He would go first, ride down to a stopping point, and radio for the next person to follow him.

Mako disappeared over the lip. I panicked, worrying that I’d make a total fool of myself; that I’d plunge into a ravine; that I’d be too petrified to have any fun, when I’d traveled all this way. Breathe, I told myself. Breathe. Then I remembered something that Alex, the pro snowboarder, had told me. An important difference between snowsurfing and snowboarding has to do with simplicity: It’s all about the turn, and not much else.

“There’s a heightened level of mastery in Japanese culture,” he’d said. “When someone gets a job, they stick at it for the rest of their life, to be the best person at that job that’s ever existed. For us in the States, when you first start out snowboarding, step one is learning how to use your edges to turn. As soon as you learn step one, you move on. You can go to the half-pipe or the trick park. But in Japan, guys will stay at step one for a long time. Even a lifetime. It blew my mind when I realized what was going on over there.”

One person went over the lip, then another. My personal goal was a perfect turn, or maybe a couple good turns at high speed, making one of those elegant S lines you see in ski films. Mako called my name over the radio. I stood up, legs shaking, said a lot of curse words under my breath, and dropped into the gully.

Photo by Kari Medig

I did not crash and burn. In fact, the steepest portion wasn’t as long as I feared, and I quickly descended into a glen. I carved through a birch grove, then flew through an open glade. The snow was pristine, untouched, several feet deep, akin to cream cheese, but drier. Almost like buoyant fog. I linked one turn after another and couldn’t keep the smile off my face. It was one of the most fluid experiences of my life. I wasn’t limited by gravity, my physical body, even time; the faster I went, the slower it felt. One turn would become another, as though the line I was meant to follow was already there.

When I reached Mako and the others, everyone was clapping and shouting. I’d realize later that they do this for everyone. It’s a marvelous feature of the Japanese snowsurf experience that a group will cheer for each person, shouting things like “Style!” or “Saiko!” (translation: awesome!) when someone makes an especially refined turn, or sprays snow as if slashing through a wave—but for the moment I thought it was just for me. Because now I got it. Not to go all touchy-feely here, and I’ll admit to cringing as I write this, but when surfers prattle on about “flow,” it’s not just talk.

Later that afternoon, I rested my aching muscles in a nearby onsen. Just me and two elderly Japanese men, naked in a dark outdoor pool fed by underground springs, surrounded by boulders, trees, and five-foot walls of snow. Steam rose from the water. We looked like snow monkeys, grunting in the mist. On Yōtei, it had taken five pitches of snowboarding to reach the base of the mountain it had taken us more than five hours to climb. The runs were stupendous, visibility clear, snow consistent. All style, occasionally saiko. At the end, if it looked like I was praying when I knelt, grinning, one final time to undo my bindings next to the van, my devotion was sincere. >>Next: Why You Should Go to Hokkaido in Winter—Even if You’re Not a Skier