We stand in front of a gold-framed Italian Renaissance painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It features a ruddy-faced white baby with impossibly fluffy curls and a wan mother draped in a dark cloth who looks like she’s had the life sucked out of her. “What about this one?” I ask Maya, my nine-year-old daughter.

Maya ponders a painting in the Met.

Photo by Courtney E. Martin

Her green eyes take it in. She’s grown so impossibly tall all of a sudden, a fawn still adjusting to her own long legs. She launches in: “This is Baby Marlow and his mother, Prue, and they are being haunted by a zombie cheerleader who, at this very moment, happens to be outside of their front door . . . ”

Maya and I move around the Met like this, one painting at a time. We pause, she tells me the story behind the painting—all the action just out of the frame, all the swirling emotions detectable in the brushstrokes and color choices.

Our little game emerged spontaneously when she said, “Momma, all these paintings look like frozen stories—like a scene that got captured.”

“They do, don’t they?” Then, pointing at one nearby, I asked, “What do you think the story is of this one?” And on we went.

Twenty years ago, I used to bust out of my Barnard dorm and walk across Central Park, arriving at the Met for a study break. I would spend hours wandering around until my feet hurt too bad to keep going. I never once imagined what it would be like to take my own daughter here. I still felt like a lost daughter, myself—that peculiar 18-year-old mix of brazen and terrified, uprooted from the only home I’d ever known in Colorado Springs.

In time, I would become of the city in a way that surprised even me. All my friends in Colorado rolled their eyes at my all-black outfits and envied my easy access to all of our favorite hip-hop groups: The Roots, Common, Black Star. After graduating in 2002, I moved to Brooklyn, myself; I would spend the next 10 years around Prospect Park, eventually finding myself in historically Caribbean Lefferts Gardens, where beef patties and banana pudding kept me fueled for all of my freelance hustling and late nights with friends.

When I got pregnant with Maya in my early 30s, and my husband, John, got a job offer in the Bay Area, we crammed our tortoiseshell cat into a black bag, stuck her under the seat of an airplane, and headed west. I was reluctant to leave my New York life, but I was also tired of hauling 25-pound bags of cat litter from Atlantic Center to my apartment. John assured me that Oakland would feel like Brooklyn, but maybe a little easier, and he was right in so many ways.

As it would turn out, it wasn’t Oakland that would feel most foreign, but my new role as a mother. It was an existential before/after moment. Before I became a mother, I was one person. A person who lived in New York. A person who didn’t own a car, much less a car seat. My time was mostly my own, even if I didn’t fully understand that then. I got tired, wrung out, overwhelmed, but recovery was always within close reach.

A decade after I left New York, Maya and I rediscovered it together.

Photo by Courtney E. Martin

And then I had Maya. And I became a different person. Or as Clare Vaye Watkins puts it in her devastating novel about new motherhood, I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness: “There was much about these thresholds that was impossible to describe from the other side. . . . I found it to be a demolishing, a taking down to the studs.”

I moved to the West Coast and was taken down to the studs. And then I rebuilt myself day by day, month by month, year by year in the shade of eucalyptus trees and the sound of broken car windows crunching underfoot. Yes, I still knew how to report a story and find a fabulous vintage shirt in any Goodwill. But I also became a person who knew how to pick a ripe loquat from the neighbor’s tree and nurse a baby. A person whose time was only my own in the tiniest of stolen moments. A person whose exhaustion was bone deep. A person whose biggest preoccupation was no longer my ambition, but my delight in my children—and my resentment at how caring for them transformed a life I had spent a lot of time building.

As my daughter grew, I realized that I wanted her to know all of me. Not just the maternal part of me, but the wandering, wondering, subway-riding, fully-at-home in the big city part of me, too. But you can never really go back, right? And can a child ever really see the whole life of her own mother?

As Maya’s ninth birthday approached, I knew: It was time for us to take a trip together one on one.

Why?

Well, first and foremost, because I like her now. I like hanging out with her. I like the quiet between us. I like the things we share–compulsion to make art, Kate DiCamillo novels, nature documentaries. I even like the things we don’t share—she’s more precise than I am, knows what she wants and how she wants it, instinctively. I also had this strong sense that because we’d mostly weathered the pandemic together—John worked outside the house and her little sister went to preschool most of the time—we deserved an adventure outside of our 1,200-square-foot home.

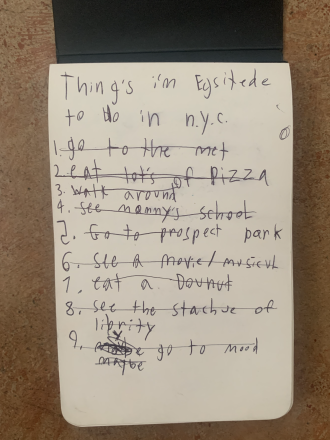

Maya wrote an itinerary for our trip.

Photo by Courtney E. Martin

When I asked her where she wanted to go, she didn’t skip a beat before saying: New York.

I let Maya be fully in charge of the itinerary, which she seemed to create with ease—both because she is discerning by nature but also because her life has been filled with cultural touchstones of New York City, such as Knuffle bunny books and Home Alone II and maybe too many stories from me about my glorious twenties. She had characteristic clarity on what she wanted to prioritize: the Met, Mood (the fabric store she’d seen on Project Runway), a Broadway show, and the Statue of Liberty. She’d also like to eat pizza. A lot of it. It sounded pretty perfect to me.

And it was. When we walked into her first Broadway theater, my introverted, self-possessed girl said, “I would love to perform for this many people someday.”

We were wowed by the costumes, dancing, and modernization of Some Like It Hot. When a huge crowd gave J. Harrison Ghee a roaring standing ovation for their incredible song about gender fluidity, I burst into tears and Maya only rolled her eyes a tiny bit.

Mood was appropriately intimidating for two gals who have no idea how to sew, but we wandered the cramped aisles marveling at all the textures and patterns, and eventually worked up the nerve to buy a little fabric and some zippers. Maya seemed equally mesmerized by the people walking around—FIT students with impossibly tall shoes and older women in hijabs chatting in front of the silks.

I steered her toward the Staten Island Ferry version of the Statue of Liberty experience, hoping that we wouldn’t spend a whole day in a tourist trap. The wind whipped around us as she tried to get a shot of Lady Liberty with her Polaroid camera. She was just a tiny dot on the ocean, but Maya didn’t seem to care. She was deliriously happy with the quest itself.

Pizza featured heavily in our trip to New York.

Photo by Courtney E. Martin

My dear friend, Anna, a single woman without kids, let us crash in her apartment in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn. As I watched Maya take in Anna’s beautiful space, Anna’s beautiful existence, I knew she was imbibing a powerful lesson about how many ways there are to compose a life. Anna’s walls are covered with art from her many travels—images from India (where her parents hail from), a Japanese woodblock print, and a photograph by French photographer JR. We three put mud masks on, snuggled up, and watched a movie, the city lights shining through Anna’s floor-to-ceiling corner windows.

I deliberately made this trip about Maya, not myself, but I did give her a glimpse into my personal history. I pointed out the New York Public Library where I wrote my first book in the Rose Reading Room before it had Wi-Fi. I popped into the Strand with her and bought her a graphic novel. We ate a slice of pizza as big as her torso at Koronet’s, my favorite spot for a 2 a.m. slice with my friends after a night out.

It’s true what they say: You can never really go back. I’ll never be 27 again, power walking to a bar to meet my friends, unaware of what it feels like to be responsible for another human being’s survival. But while in New York with this little person I have kept alive, I realized, you can be a mother and be whole.

Maya and I sit squished together on the orange plastic seats of the 2 train. I watch strangers after so many years of pandemic claustrophobia. She reaches for one of my ear buds and sticks it in her left ear, where a tiny shark tooth earring dangles. My right ear is already filled with the sounds of the playlist we’ve made together for our special trip. As the beat drops on the first few notes of Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind,” I lean against her and squeeze her hand. She looks up and gives me a wide smile. She sees me.

How to experience NYC with a kid

Traveling to NYC with your kid? Use these tips.

Let them create the itinerary.

If they don’t know much about NYC, that’s OK. Write a bunch of experiences on sticky notes and let them arrange them on a big board. You can help them be realistic about how much is possible in a given day.

Turn transportation into a math lesson

Maya and I bought one weeklong subway pass and then recorded every single ride we took in a little notebook. At the end we calculated whether the weeklong pass had been worth it. The answer was . . . almost—but we decided that the people-watching was priceless.

Speaking of transportation, ride the bus! Such a great way to see so much of the city when your legs need a break.

Bring a Polaroid camera and put it in your kid’s hands.

Sure, you could pass them your cell phone, but there’s nothing like the visceral experience of a Polaroid that gives you instant and always artistic shots. We also brought along a notebook, pens, and tape, so we could make our scrapbook as we went along—a great activity for the inevitable downtime.

Follow your kid’s lead in the museum.

Maya and I covered so little of the Met, but the rooms we did walk through came alive for us because she made up stories and we moved at her pace. Ask your kid questions. Don’t parentsplain them. And don’t sleep on some of the lesser-known museums: El Museo del Barrio, the Tenement Museum, and/or the New York Transit Museum, depending on your kid’s age and interest.

Don’t just settle for staid institutions; ask for recommendations and look up happenings.

When we were in NYC, one of my readers told me about a Renegade Art Fair that was taking place that weekend, so we went and had a blast.

Don’t avoid the big touristy spots just because you think they’re basic.

Your kid deserves to experience the Big Apple with wide, naive eyes. Times Square was way too much for my nervous system, but I loved watching Maya take it in for the first time. She wanted nothing more than to buy a snow globe. So be it! There’s no fun in forcing your definition of sophistication on your kids. They have the rest of their lives to get cool and cynical.

![A garden in Detroit, Michigan with a mural by <a href="https://www.aylonomad.com/">https://www.aylonomad.com/</a> and <a href="https://www.cbloxx.co.uk/" target="_blank" link-data="{"cms.site.owner":{"_ref":"00000180-8bd0-dd55-a3eb-9bd4fc3b0000","_type":"ae3387cc-b875-31b7-b82d-63fd8d758c20"},"cms.content.publishDate":1747847556787,"cms.content.publishUser":{"_ref":"00000181-6fc4-d340-a795-efe797f20000","_type":"6aa69ae1-35be-30dc-87e9-410da9e1cdcc"},"cms.content.updateDate":1747847556787,"cms.content.updateUser":{"_ref":"00000181-6fc4-d340-a795-efe797f20000","_type":"6aa69ae1-35be-30dc-87e9-410da9e1cdcc"},"link":{"target":"NEW","attributes":[],"url":"https://www.cbloxx.co.uk/","_id":"00000196-f3d4-df3a-a9fe-fbdc1b9a0000","_type":"33ac701a-72c1-316a-a3a5-13918cf384df"},"_id":"00000196-f3d4-df3a-a9fe-fbdc1b850000","_type":"02ec1f82-5e56-3b8c-af6e-6fc7c8772266"}">Cbloxx</a> of <a href="https://www.nomadclan.co.uk/" target="_blank" link-data="{"cms.site.owner":{"_ref":"00000180-8bd0-dd55-a3eb-9bd4fc3b0000","_type":"ae3387cc-b875-31b7-b82d-63fd8d758c20"},"cms.content.publishDate":1747847582810,"cms.content.publishUser":{"_ref":"00000181-6fc4-d340-a795-efe797f20000","_type":"6aa69ae1-35be-30dc-87e9-410da9e1cdcc"},"cms.content.updateDate":1747847582810,"cms.content.updateUser":{"_ref":"00000181-6fc4-d340-a795-efe797f20000","_type":"6aa69ae1-35be-30dc-87e9-410da9e1cdcc"},"link":{"target":"NEW","attributes":[],"url":"https://www.nomadclan.co.uk/","_id":"00000196-f3d5-de7f-a3de-f3ff80280000","_type":"33ac701a-72c1-316a-a3a5-13918cf384df"},"_id":"00000196-f3d5-de7f-a3de-f3ff80140000","_type":"02ec1f82-5e56-3b8c-af6e-6fc7c8772266"}">Nomad Clan</a> in the background](https://afar.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/e7be549/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3000x1684+0+192/resize/490x275!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fk3-prod-afar-media.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com%2Fbrightspot%2Feb%2Fe4%2F8f738c8149ae81425d0101e9a945%2Fafar-riverwalk-sylviajarrus-2024.jpg)